| PREV - BACK - NEXT |

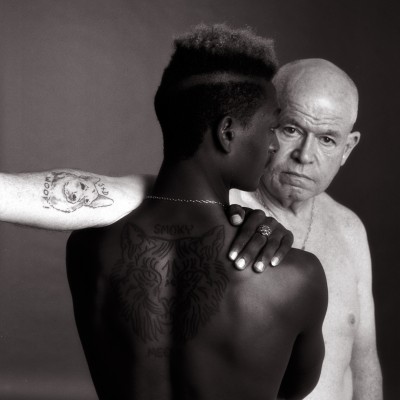

2+2 = 2 Jews & 2 Tattoos The awkward, Kafkaesque ballet between age and beauty in the eleven photographs that comprise 2+2 presents an ironic record of an absurd collision of co-incidences, and atrocities, stretching across time. This series of works by Vanessa Franklin also tells the story of two men brought together. One, a Falasha from Ethiopia, is a black Jew, the other, a Sephardic Jew from Japan, is what the writer James Baldwin, a close friend of the subject’s aunt, used to describe tongue-in-cheek as ‘a white nigger’. The Falasha claim descent from the Ethiopian Emperor Menelek I, traditionally thought to be the son of the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, and remained faithful to Judaism even after his empire converted to Christianity. Since the 4th century they have suffered many persecutions, pogroms and indignities - many now live in Israel. The Sephardim, Jewish communities who coalesced in North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula about 1,000 years ago, lived in harmony with the Moors but were persecuted systematically by the Spanish Inquisition until the Catholics drove them out in 1492. Some fled South for their lives to Africa, others to the Balkans and West Asia, still others followed the Spice Route and established communities in Cochin, on the South-West coast of India, and further East. Within living memory, many millions of Jewish people were murdered in the Shoah. In the concentration camps, victims were dehumanised, ordered and recognised by the tattoos on their arms. Franklin discovered this aged 13 when, as part of the preparation for her bat mitzvah, Rabbi Katzmann rolled up his sleeve. But it was only much later that she found out that her great grandmother, a Sephardic Jew from Thessaloniki, had perished – yet another number on an arm in Auschwitz. Until this realisation, a pall of guilt and silence had inexplicably covered this poor woman’s memory. Today, two Jews, with two tattoos, and one photographer, move on but never forget. Ostensibly, 2+2 is a sardonic celebration of newly made tattoos devised by British artists, Jake and Dinos Chapman. One, a ridiculous image of Blondie, Adolf Hitler’s much-loved Alsatian dog, adorns the inside of a white arm. The other, a larger rendering of Smoky, Benito Mussolini’s apocryphal bobcat, stretches across a black back.[1] Although inked by master tattooists, these kitsch representations retain the stench of criminality, made even more loathsome and ridiculous by the banal legends beneath them: ‘Woof!’ and ‘Meow!’ Alone, or together, this tale of cat and dog is subsumed within the Manichean presence of the two people into whose skin they are cut as they struggle, twirl, embrace, or stand alone. But their humanity, vulnerability - and love – render the toxic dogmas these dumb animals represent sad, powerless and irrelevant. The idea of a tattoo as both a punishment and redemption of guilt that this work confronts was prefigured in a short story written in 1914 by Franz Kafka, a German-speaking Jew living in Prague. The elaborate torture and execution device at the heart of In the Penal Colony tattoos their crime onto the skin of the condemned as they meet an excruciatingly slow but ecstatic death – a solution that even Kafka himself finally rejects. The formula of this collaborative work, however, suggests a different pattern: the absurd synergy between punishment and redemption has now been decisively broken. And out of its fragments an implacable peal of laughter resounds. David Elliott Berlin, 7th June 2017 |